Incremental Processing on the Data Lake

NOTE: This article is a translation of the infoq.cn article, found here, with minor edits

Apache Hudi is a data lake framework which provides the ability to ingest, manage and query large analytical data sets on a distributed file system/cloud stores. Hudi joined the Apache incubator for incubation in January 2019, and was promoted to the top Apache project in May 2020. This article mainly discusses the importance of Hudi to the data lake from the perspective of "incremental processing". More information about Apache Hudi's framework functions, features, usage scenarios, and latest developments can be found at QCon Global Software Development Conference (Shanghai Station) 2020.

Throughout the development of big data technology, Hadoop has steadily seized the opportunities of this era and has become the de-facto standard for enterprises to build big data infrastructure. Among them, the distributed file system HDFS that supports the Hadoop ecosystem almost naturally has become the standard interface for big data storage systems. In recent years, with the rise of cloud-native architectures, we have seen a wave of newer models embracing low-cost cloud storage emerging, a number of data lake frameworks compatible with HDFS interfaces embracing cloud vendor storage have emerged in the industry as well.

However, we are still processing data pretty much in the same way we did 10 years ago. This article will try to talk about its importance to the data lake from the perspective of "incremental processing".

Traditional data lakes lack the primitives for incremental processing

In the era of mobile Internet and Internet of Things, delayed arrival of data is very common. Here we are involved in the definition of two time semantics: event time and processing time.

As the name suggests:

- Event time: the time when the event actually occurred;

- Processing time: the time when an event is observed (processed) in the system;

Ideally, the event time and the processing time are the same, but in reality, they may have more or less deviation, which we often call "Time Skew". Whether for low-latency stream computing or common batch processing, the processing of event time and processing time and late data is a common and difficult problem. In general, in order to ensure correctness, when we strictly follow the "event time" semantics, late data will trigger the recalculation of the time window (usually Hive partitions for batch processing), although the results of these "windows" may have been calculated or even interacted with the end user. For recalculation, the extensible key-value storage structure is usually used in streaming processing, which is processed incrementally at the record/event level and optimized based on point queries and updates. However, in data lakes, recalculating usually means rewriting the entire (immutable) Hive partition (or simply a folder in DFS), and re-triggering the recalculation of cascading tasks that have consumed that Hive partition.

With data lakes supporting massive amounts of data, many long-tail businesses still have a strong demand for updating cold data. However, for a long time, the data in a single partition in the data lake was designed to be non-updatable. If it needs to be updated, the entire partition needs to be rewritten. This will seriously damage the efficiency of the entire ecosystem. From the perspective of latency and resource utilization, these operations on Hadoop will incur expensive overhead. Besides, this overhead is usually also cascaded to the entire Hadoop data processing pipeline, which ultimately leads to an increase in latency by several hours.

In response to the two problems mentioned above, if the data lake supports fine-grained incremental processing, we can incorporate changes into existing Hive partitions more effectively, and provide a way for downstream table consumers to obtain only the changed data. For effectively supporting incremental processing, we can decompose it into the following two primitive operations:

-

Update insert (upsert): Conceptually, rewriting the entire partition can be regarded as a very inefficient upsert operation, which will eventually write much more data than the original data itself. Therefore, support for (bulk) upsert is considered a very important feature. Google's Mesa (Google's data warehouse system) also talks about several techniques that can be applied to rapid data ingestion scenarios.

-

Incremental consumption: Although upsert can solve the problem of quickly releasing new data to a partition, downstream data consumers do not know which data has been changed from which time in the past. Usually, consumers can only know the changed data by scanning the entire partition/data table and recalculating all the data, which requires considerable time and resources. Therefore, we also need a mechanism to more efficiently obtain data records that have changed since the last time the partition was consumed.

With the above two primitive operations, you can upsert a data set, and then incrementally consume from it, and create another (also incremental) data set to solve the two problems we mentioned above and support many common cases, so as to support end-to-end incremental processing and reduce end-to-end latency. These two primitives combine with each other, unlocking the ability of stream/incremental processing based on DFS abstraction.

The storage scale of the data lake far exceeds that of the data warehouse. Although the two have different focuses on the definition of functions, there is still a considerable intersection (of course, there are still disputes and deviations from definition and implementation. This is not the topic this article tries to discuss). In any case, the data lake will support larger analytical data sets with cheaper storage, so incremental processing is also very important for it. Next let's discuss the significance of incremental processing for the data lake.

The significance of incremental processing for the data lake

Streaming Semantics

It has long been stated that there is a "dualism" between the change log (that is, the "flow" in the conventional sense we understand) and the table.

The core of this discussion is: if there is a change log, you can use these changes to generate a data table and get the current status. If you update a table, you can record these changes and publish all "change logs" to the table's status information. This interchangeable nature is called "stream table duality" for short.

A more general understanding of "stream table duality": when the business system is modifying the data in the MySQL table, MySQL will reflect these changes as Binlog, if we publish these continuous Binlog (stream) to Kafka, and then let the downstream processing system subscribe to the Kafka, and use the state store to gradually accumulate the intermediate results. Then the current state of this intermediate result can reflects the current snapshot of the table.

If the two primitives mentioned above that support incremental processing can be introduced to the data lake, the above pipeline, which can reflect the "stream table duality", is also applicable on the data lake. Based on the first primitive, the data lake can also ingest the Binlog log streams in Kafka, and then store these Binlog log streams into "tables" on the data lake. Based on the second primitive, these tables recognize the changed records as "Binlog" streams to support the incremental consumption of subsequent cascading tasks.

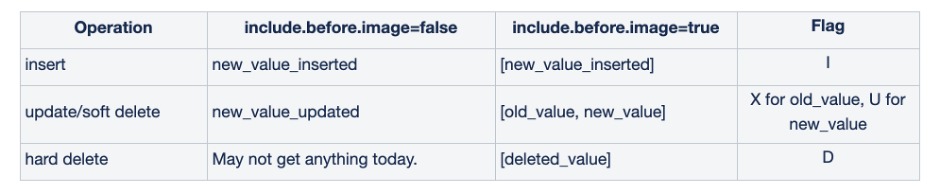

Of course, as the data in the data lake needs to be landed on the final file/object storage, considering the trade-off between throughput and write performance, Binlog on the data lake reacts to a small batch of change logs over a period of time on the stream. For example, the Apache Hudi community is further trying to provide an incremental view similar to Binlog for different Commits (a Commit refers to a batch of data write commit), as shown in the following figure:

Remarks in the "Flag" column:

I: Insert; D: Delete; U: After image of Update; X: Before image of Update;

Based on the above discussion, we can think that incremental processing and stream are naturally compatible, and we can naturally connect them on the data lake.

Warehousing needs Incremental Processing

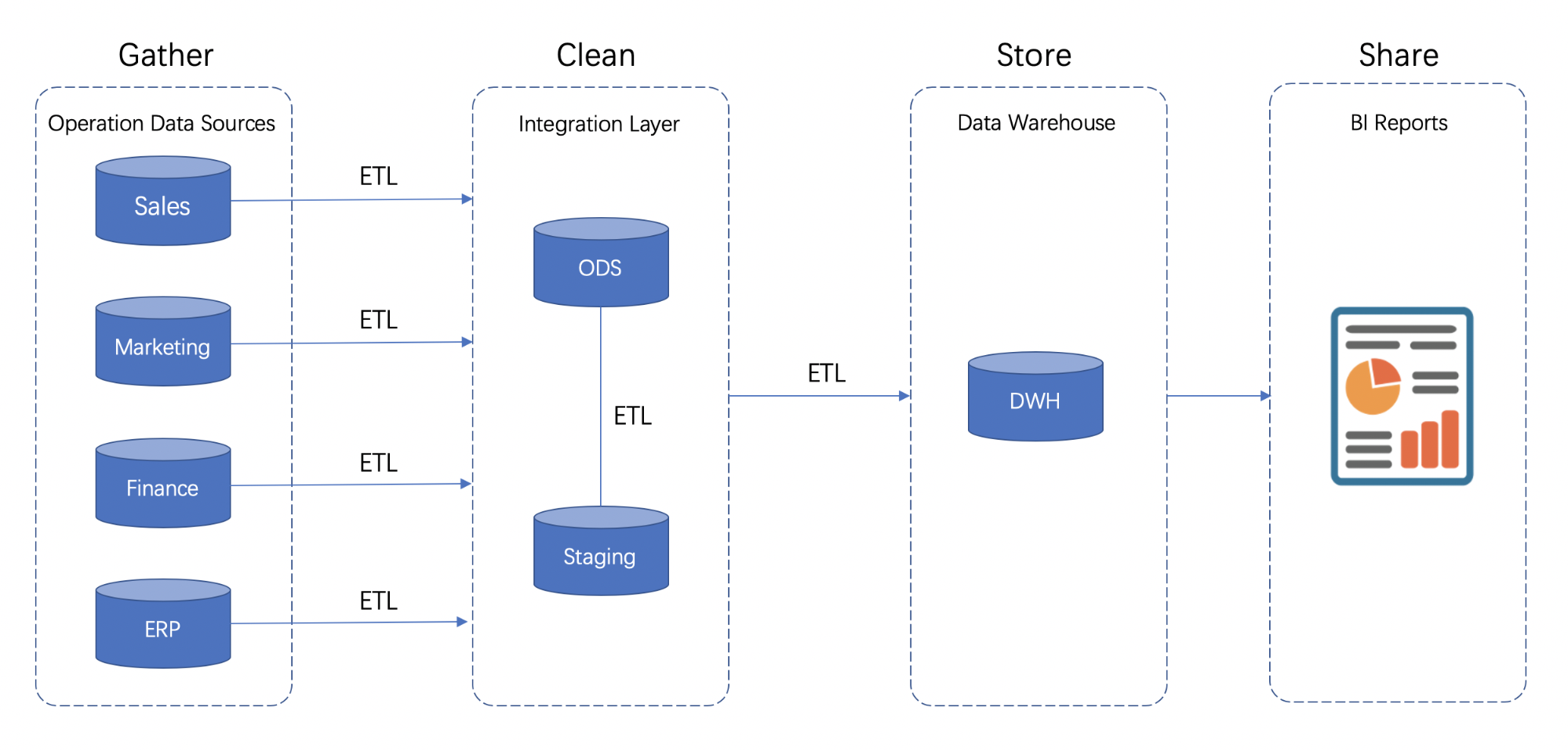

In the data warehouse, whether it is dimensional modeling or relational modeling theory, it is usually constructed based on the layered design ideas. In terms of technical implementation, multiple stages (steps) of a long pipeline are formed by connecting multiple levels of ETL tasks through a workflow scheduling engine, as shown in the following figure:

As the main application of the data warehouse, in the OLAP field, for the conventional business scenarios(for no or few changes), there are already some frameworks in the industry that focus on the scenarios where they are good at providing efficient analysis capabilities. However, in the Hadoop data warehouse/data lake ecosystem, there is still no good solution for the analysis scenario of frequent changes of business data.

For example, let’s consider the scenario of updating the order status of a travel business. This scenario has a typical long-tail effect: you cannot know whether an order will be billed tomorrow, one month later, or one year later. In this scenario, the order table is the main data table, but usually we will derive other derived tables based on this table to support the modeling of various business scenarios. The initial update takes place in the order table at the ODS level, but the derived tables need to be updated in cascade.

For this scenario, in the past, once there is a change, people usually need to find the partition where the data to be updated is located in the Hive order table of the ODS layer, and update the entire partition, besides, the partition of the relevant data of the derived table needs to be updated in cascade.

Yes, someone will definitely think of that Kudu's support for Upsert can solve the problem of the old version of Hive missing the first incremental primitive. But the Kudu storage engine has its own limitations:

- Performance: additional requirements for the hardware itself;

- Ecologically: In terms of adapting to mainstream big data computing frameworks and machine learning frameworks, it is far less advantageous than Hive;

- Cost: requires special maintenance costs and expenses;

- Did not solve the second primitive of incremental processing mentioned above: the problem of incremental consumption.

In summary, incremental processing has the following advantages on the data lake:

Performance improvement: Ingesting data usually needs to handle updates, deletes, and enforce unique key constraints. Since incremental primitives support record-level updates, it can bring orders of magnitude performance improvements to these operations.

Faster ETL/derived Pipelines: An ubiquitous next step, once the data has been ingested from external sources is to build derived data pipelines using Apache Spark/Apache Hive or any other data processing framework to ETL the ingested data for a variety of use-cases like data warehouse, machine learning, or even just analytics. Typically, such processes again rely on batch processing jobs expressed in code or SQL. Such data pipelines can be speed up dramatically, by querying one or more input tables using an incremental query instead of a regular snapshot query, resulting in only processing the incremental changes from upstream tables and then upsert or delete the target derived table.Similar to raw data ingestion, in order to reduce the data delay of the modelled table, the ETL job only needs to gradually extract the changed data from the original table and update the previously derived output table instead of rebuilding the entire output table every few hours .

Unified storage: Based on the above two advantages, faster and lighter processing on the existing data lake means that only for the purpose of accessing near real-time data, no special storage or data mart is needed.

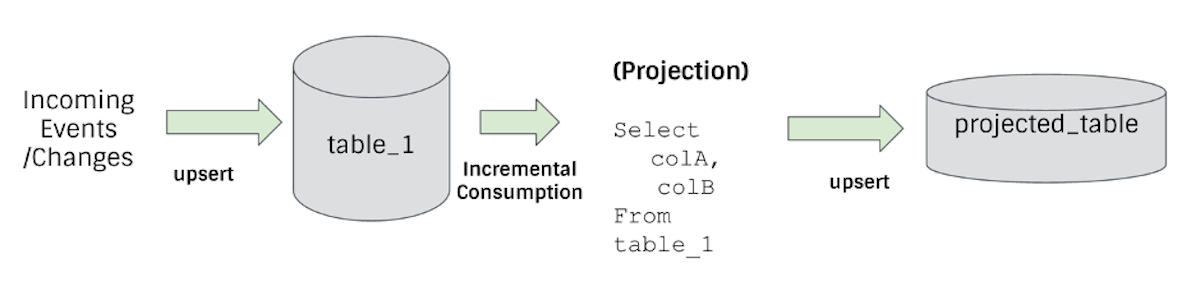

Next, we use two simple examples to illustrate how incremental processing can speed up the processing of pipelines in analytical scenarios. First of all, data projection is the most common and easy to understand case:

This simple example shows that: by upserting new changes into table_1 and establishing a simple projected table (projected_table) through incremental consumption, we can operate simpler with lower latency more efficiently projection.

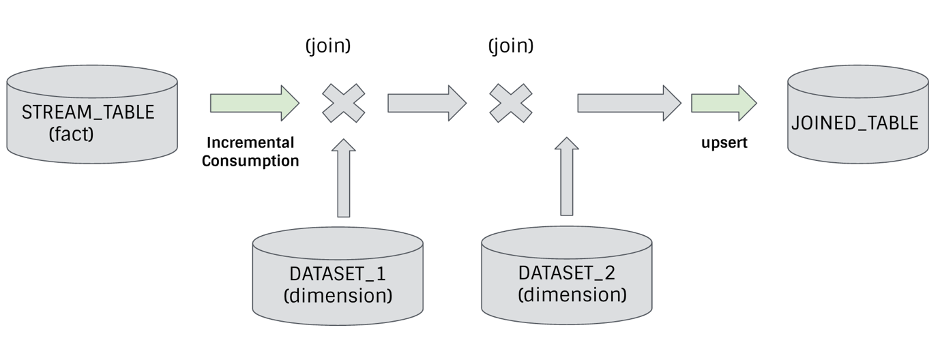

Next, for a more complex scenario, we can use incremental processing to support the stream and batch connections supported by the stream computing framework, and stream-stream connections (just need to add some additional logic to align window) :

The example in the figure above connects a fact table to multiple dimension tables to create a connected table. This case is one of the rare scenarios where we can save hardware costs while significantly reducing latency.

Quasi-real-time scenarios, resource/efficiency trade-offs

Incremental processing of new data in mini batches can use resources more efficiently. Let's refer to a specific example. We have a Kafka event stream that is pouring in at a rate of 10,000 per second. We want to count the number of messages in some dimensions over the past 15 minutes. Many stream processing pipelines use an external/internal result state store (such as RocksDB, Cassandra, ElasticSearch) to save the aggregated count results, and run the containers in resource managers such as YARN/Mesos continuously, which is very reasonable in less than a five-minute delay window scene. In fact, the YARN container itself has some startup overhead. In addition, in order to improve the performance of writing to result storage system, we usually cache the results before performing batch updates. This kind of protocol requires the container to run continuously.

However, in quasi-real-time processing scenarios, these options may not be optimal. To achieve the same effect, you can use short-life containers and optimize overall resource utilization. For example, a streaming processor may need to perform six million updates to the result storage system in 15 minutes. However, in the incremental batch mode, we only need to perform an in-memory merge on the accumulated data and update the result storage system only once, then only use the resource container for five minutes. Compared with the pure stream processing mode, the incremental batch processing mode has several times the CPU efficiency improvement, and there are several orders of magnitude efficiency improvement in updating to the result storage. Basically, this processing method obtains resources on demand, instead of swallowing CPU and memory while waiting for data to be calculated in real time.

Incremental processing facilitates unified data lake architecture

Whether in the data warehouse or in the data lake, data processing is an unavoidable problem. Data processing involves the selection of computing engines and the design of architectures. There are currently two mainstream architectures in the industry: Lambda and Kappa architectures. Each architecture has its own characteristics and existing problems. Derivative versions of these architectures are also emerging endlessly.

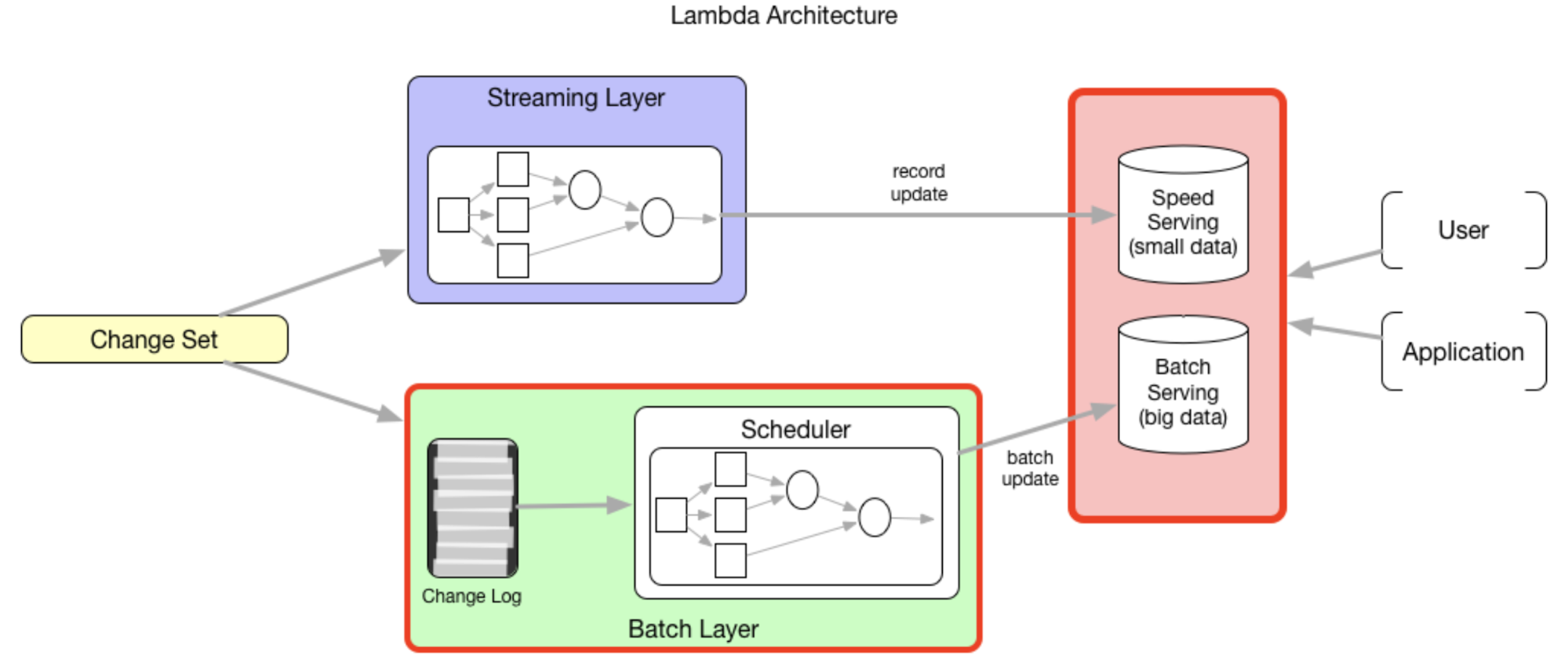

In reality, many enterprises still maintain the implementation of the Lambda architecture. The typical Lambda architecture has two modules for the data processing part: the speed layer and the batch layer.

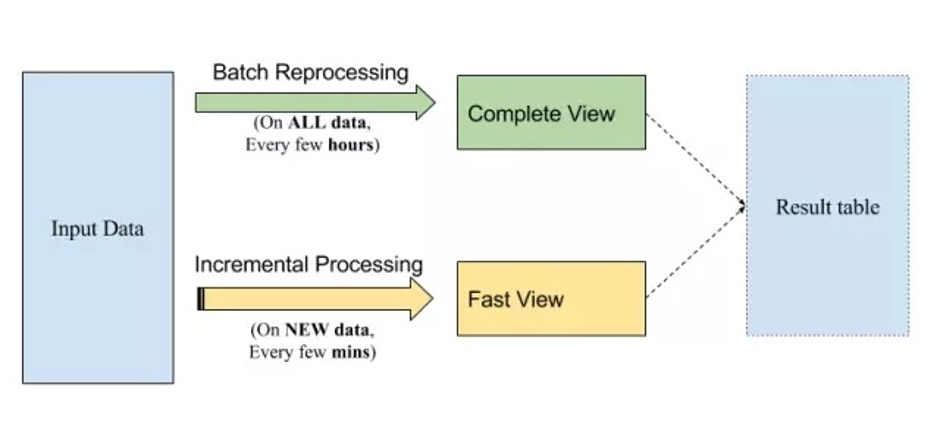

They are usually two independent implementations (from code to infrastructure). For example, Flink (formerly Storm) is a popular option on the speed layer, while MapReduce/Spark can serve as a batch layer. In fact, people often rely on the speed layer to provide updated results (which may not be accurate), and once the data is considered complete, the results of the speed layer are corrected at a later time through the batch layer. With incremental processing, we have the opportunity to implement the Lambda architecture for batch processing and quasi-real-time processing at the code level and infrastructure level in a unified manner. It typically looks like below:

As we said, you can use SQL or a batch processing framework like Spark to consistently implement your processing logic. The result table is built incrementally, and SQL is executed on "new data" like streaming to produce a quick view of the results. The same SQL can be executed periodically on the full amount of data to correct any inaccurate results (remember, join operations are always tricky!) and produce a more "complete" view of the results. In both cases, we will use the same infrastructure to perform calculations, which can reduce overall operating costs and complexity.

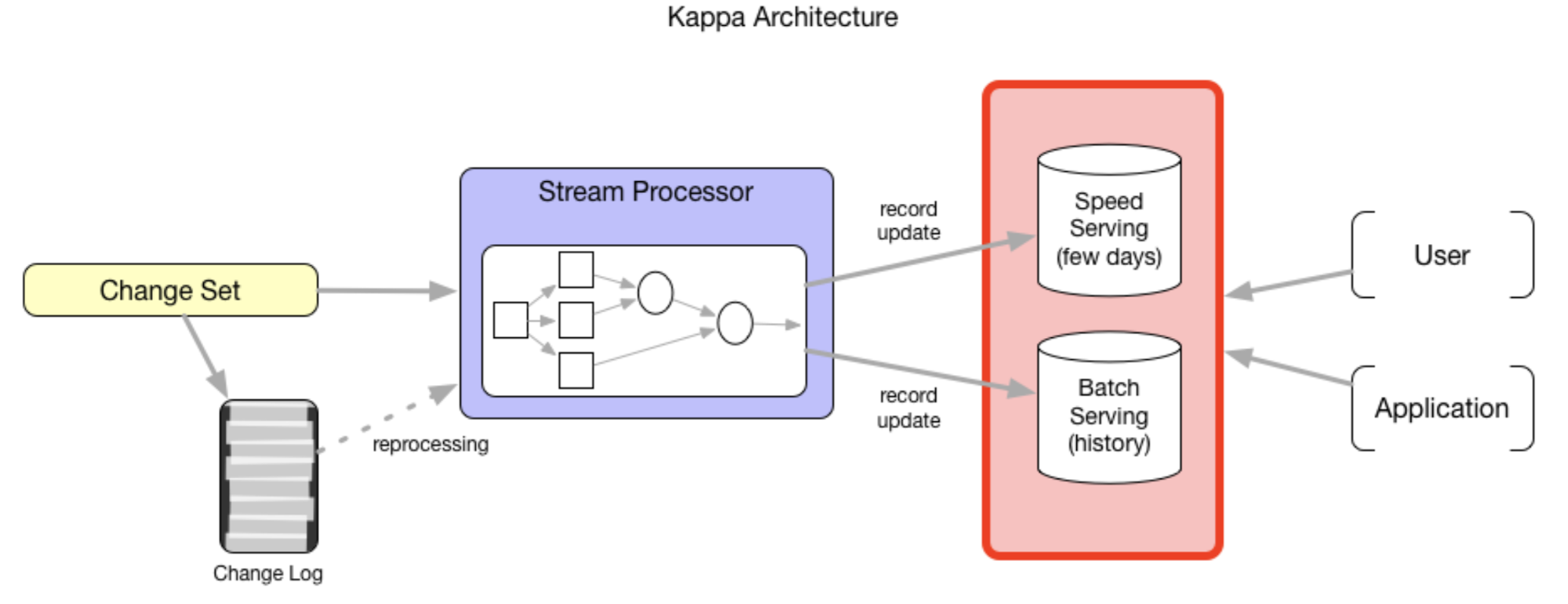

Setting aside the Lambda architecture, even in the Kappa architecture, the first primitive of incremental processing (upsert) also plays an important role. Uber proposed the Kappa + architecture based on this. The Kappa architecture advocates a single stream computing layer sufficient to become a general solution for data processing. Although the batch layer is removed in this model, there are still two problems in the service layer:

Now days many stream processing engines support row-level data processing, which requires that our service layer should also support row-level updates; The trade-offs between data ingestion delay, scanning performance and computing resources and operational complexity are unavoidable.

However, if our business scenarios have low latency requirements, for example, we can accept a delay of about 10 minutes. And if we can quickly ingest and prepare data on DFS, effectively connect and propagate updates to the upper-level modeling data set, Speed Serving in the service layer is unnecessary. Then the service layer can be unified, greatly reducing the overall complexity and resource consumption of the system.

Above, we introduced the significance of incremental processing for the data lake. Next, we introduce the implementation and support of incremental processing. Among the three open source data lake frameworks (Apache Hudi/Iceberg, Delta Lake), only Apache Hudi provides good support for incremental processing. This is completely rooted in a framework developed by Uber at the time when it encountered the pain points of data analysis on the Hadoop data lake. So, next, let's introduce how Hudi supports incremental processing.

Hudi's support for incremental processing

Apache Hudi (Hadoop Upserts Deletes and Incrementals) is a top-level project of the Apache Foundation. It allows you to process very large-scale data on top of Hadoop-compatible storage, and it also provides two primitives that enable stream processing on the data lake in addition to classic batch processing.

From the naming of the letter "I" denotes "Incremental Processing", we can see that it will support incremental processing as a first class citizen. The two primitives we mentioned at the beginning of this article that support incremental processing are reflected in the following two aspects in Apache Hudi:

Update/Delete operation:Hudi provides support for updating/deleting records, using fine-grained file/record level indexes while providing transactional guarantees for the write operation. Queries process the last such committed snapshot, to produce results..

Change stream: Hudi also provides first-class support for obtaining an incremental stream of all the records that were updated/inserted/deleted in a given table, from a given point-in-time.

The specific implementation of the change flow is "incremental view". Hudi is the only one of the three open source data lake frameworks that supports the incremental query feature, with support for record level change streams. The following sample code snippet shows us how to query the incremental view:

// spark-shell

// reload data

spark.

read.

format("hudi").

load(basePath + "/*/*/*/*").

createOrReplaceTempView("hudi_trips_snapshot")

val commits = spark.sql("select distinct(_hoodie_commit_time) as commitTime from hudi_trips_snapshot order by commitTime").map(k => k.getString(0)).take(50)

val beginTime = commits(commits.length - 2) // commit time we are interested in

// incrementally query data

val tripsIncrementalDF = spark.read.format("hudi").

option(QUERY_TYPE_OPT_KEY, QUERY_TYPE_INCREMENTAL_OPT_VAL).

option(BEGIN_INSTANTTIME_OPT_KEY, beginTime).

load(basePath)

tripsIncrementalDF.createOrReplaceTempView("hudi_trips_incremental")

spark.sql("select `_hoodie_commit_time`, fare, begin_lon, begin_lat, ts from hudi_trips_incremental where fare > 20.0").show()

The code snippet above creates a Hudi trip increment table (hudi_trips_incremental), and then queries all the change records in the increment table after the "beginTime" submission time and the "cost" is greater than 20.0. Based on this query, you can create incremental data pipelines on batch data.

Summary

In this article, we first elaborated many problems caused by the lack of incremental processing primitives in the traditional Hadoop data warehouse due to the trade-off between data integrity and latency, and some long-tail applications that rely heavily on updates. Next, we argued that to support incremental processing, we must have at least two primitives: upsert and incremental consumption, and explained why these two primitives can solve the problems explained above.

Then, we introduced why incremental processing is also important to the data lake. There are many common parts in data processing between the data lake and the data warehouse. In the data warehouse, some "pain points" caused by the lack of incremental processing also exist in the data lake. We elaborated its significance to the data lake from four aspects: incremental processing of semantics of natural fit flow, the need for analytical scenarios, quasi-real-time scene resource/efficiency trade-offs, and unified lake architecture.

Finally, we introduced the open source data lake storage framework Apache Hudi's support for incremental processing and simple cases.