Concepts

Apache Hudi (pronounced “Hudi”) provides the following streaming primitives over hadoop compatible storages

- Update/Delete Records (how do I change records in a table?)

- Change Streams (how do I fetch records that changed?)

In this section, we will discuss key concepts & terminologies that are important to understand, to be able to effectively use these primitives.

Timeline

At its core, Hudi maintains a timeline of all actions performed on the table at different instants of time that helps provide instantaneous views of the table,

while also efficiently supporting retrieval of data in the order of arrival. A Hudi instant consists of the following components

Instant action: Type of action performed on the tableInstant time: Instant time is typically a timestamp (e.g: 20190117010349), which monotonically increases in the order of action's begin time.state: current state of the instant

Hudi guarantees that the actions performed on the timeline are atomic & timeline consistent based on the instant time.

Key actions performed include

COMMITS- A commit denotes an atomic write of a batch of records into a table.CLEANS- Background activity that gets rid of older versions of files in the table, that are no longer needed.DELTA_COMMIT- A delta commit refers to an atomic write of a batch of records into a MergeOnRead type table, where some/all of the data could be just written to delta logs.COMPACTION- Background activity to reconcile differential data structures within Hudi e.g: moving updates from row based log files to columnar formats. Internally, compaction manifests as a special commit on the timelineROLLBACK- Indicates that a commit/delta commit was unsuccessful & rolled back, removing any partial files produced during such a writeSAVEPOINT- Marks certain file groups as "saved", such that cleaner will not delete them. It helps restore the table to a point on the timeline, in case of disaster/data recovery scenarios.

Any given instant can be in one of the following states

REQUESTED- Denotes an action has been scheduled, but has not initiatedINFLIGHT- Denotes that the action is currently being performedCOMPLETED- Denotes completion of an action on the timeline

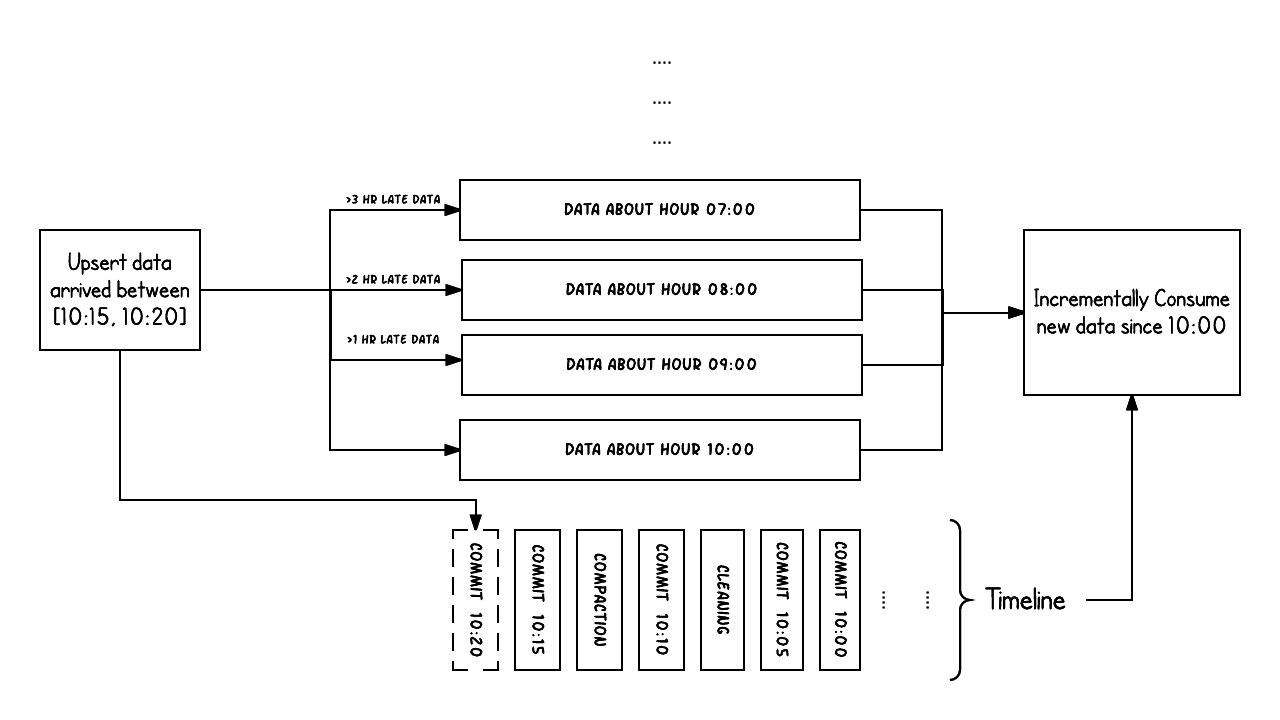

Example above shows upserts happenings between 10:00 and 10:20 on a Hudi table, roughly every 5 mins, leaving commit metadata on the Hudi timeline, along

with other background cleaning/compactions. One key observation to make is that the commit time indicates the arrival time of the data (10:20AM), while the actual data

organization reflects the actual time or event time, the data was intended for (hourly buckets from 07:00). These are two key concepts when reasoning about tradeoffs between latency and completeness of data.

When there is late arriving data (data intended for 9:00 arriving >1 hr late at 10:20), we can see the upsert producing new data into even older time buckets/folders. With the help of the timeline, an incremental query attempting to get all new data that was committed successfully since 10:00 hours, is able to very efficiently consume only the changed files without say scanning all the time buckets > 07:00.

File management

Hudi organizes a table into a directory structure under a basepath on DFS. Table is broken up into partitions, which are folders containing data files for that partition,

very similar to Hive tables. Each partition is uniquely identified by its partitionpath, which is relative to the basepath.

Within each partition, files are organized into file groups, uniquely identified by a file id. Each file group contains several

file slices, where each slice contains a base file (*.parquet) produced at a certain commit/compaction instant time,

along with set of log files (*.log.*) that contain inserts/updates to the base file since the base file was produced.

Hudi adopts a MVCC design, where compaction action merges logs and base files to produce new file slices and cleaning action gets rid of

unused/older file slices to reclaim space on DFS.

Index

Hudi provides efficient upserts, by mapping a given hoodie key (record key + partition path) consistently to a file id, via an indexing mechanism. This mapping between record key and file group/file id, never changes once the first version of a record has been written to a file. In short, the mapped file group contains all versions of a group of records.

Table Types & Queries

Hudi table types define how data is indexed & laid out on the DFS and how the above primitives and timeline activities are implemented on top of such organization (i.e how data is written).

In turn, query types define how the underlying data is exposed to the queries (i.e how data is read).

| Table Type | Supported Query types |

|---|---|

| Copy On Write | Snapshot Queries + Incremental Queries |

| Merge On Read | Snapshot Queries + Incremental Queries + Read Optimized Queries |

Table Types

Hudi supports the following table types.

- Copy On Write : Stores data using exclusively columnar file formats (e.g parquet). Updates simply version & rewrite the files by performing a synchronous merge during write.

- Merge On Read : Stores data using a combination of columnar (e.g parquet) + row based (e.g avro) file formats. Updates are logged to delta files & later compacted to produce new versions of columnar files synchronously or asynchronously.

Following table summarizes the trade-offs between these two table types

| Trade-off | CopyOnWrite | MergeOnRead |

|---|---|---|

| Data Latency | Higher | Lower |

| Update cost (I/O) | Higher (rewrite entire parquet) | Lower (append to delta log) |

| Parquet File Size | Smaller (high update(I/0) cost) | Larger (low update cost) |

| Write Amplification | Higher | Lower (depending on compaction strategy) |

Query types

Hudi supports the following query types

- Snapshot Queries : Queries see the latest snapshot of the table as of a given commit or compaction action. In case of merge on read table, it exposes near-real time data(few mins) by merging the base and delta files of the latest file slice on-the-fly. For copy on write table, it provides a drop-in replacement for existing parquet tables, while providing upsert/delete and other write side features.

- Incremental Queries : Queries only see new data written to the table, since a given commit/compaction. This effectively provides change streams to enable incremental data pipelines.

- Read Optimized Queries : Queries see the latest snapshot of table as of a given commit/compaction action. Exposes only the base/columnar files in latest file slices and guarantees the same columnar query performance compared to a non-hudi columnar table.

Following table summarizes the trade-offs between the different query types.

| Trade-off | Snapshot | Read Optimized |

|---|---|---|

| Data Latency | Lower | Higher |

| Query Latency | Higher (merge base / columnar file + row based delta / log files) | Lower (raw base / columnar file performance) |

Copy On Write Table

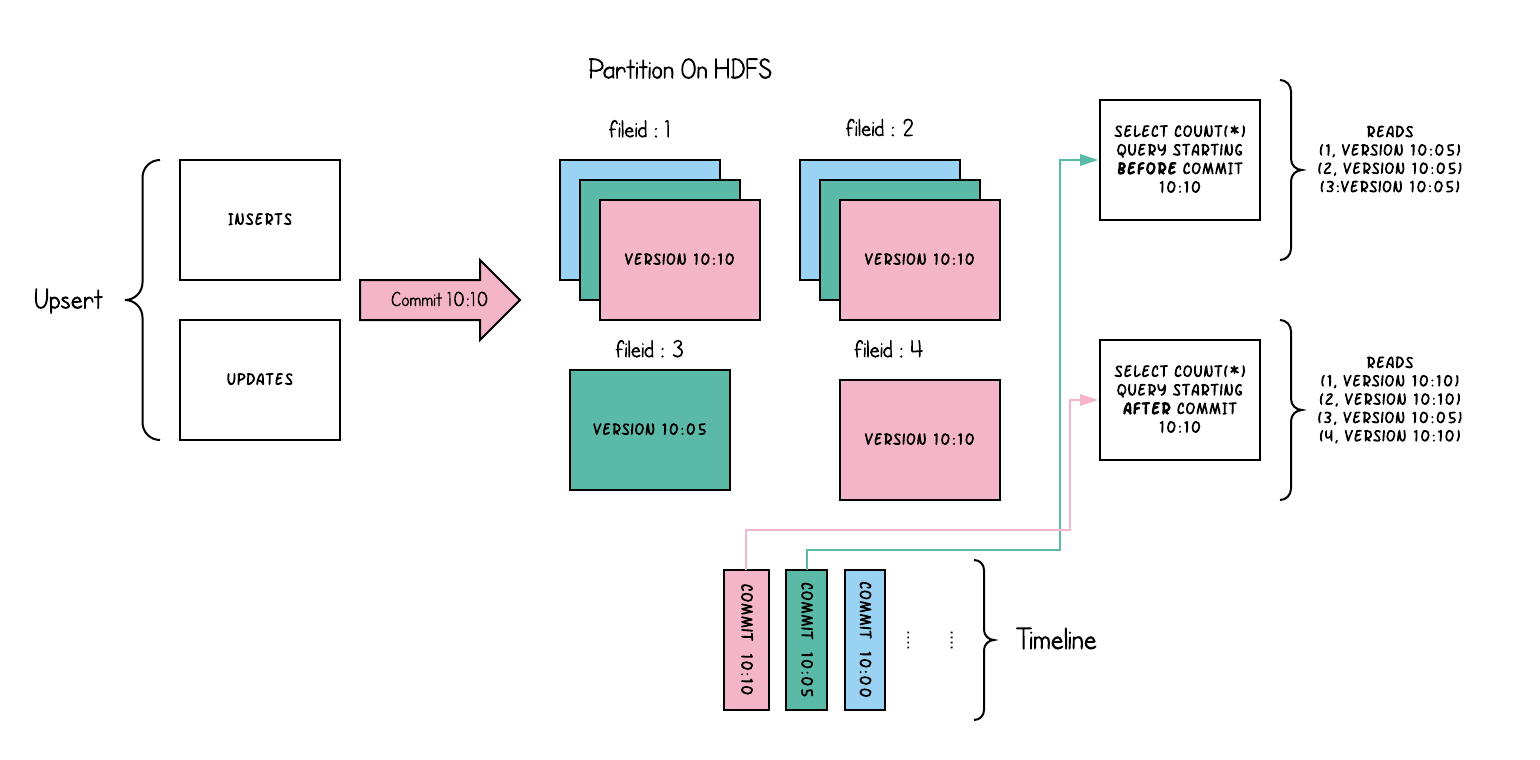

File slices in Copy-On-Write table only contain the base/columnar file and each commit produces new versions of base files. In other words, we implicitly compact on every commit, such that only columnar data exists. As a result, the write amplification (number of bytes written for 1 byte of incoming data) is much higher, where read amplification is zero. This is a much desired property for analytical workloads, which is predominantly read-heavy.

Following illustrates how this works conceptually, when data written into copy-on-write table and two queries running on top of it.

As data gets written, updates to existing file groups produce a new slice for that file group stamped with the commit instant time,

while inserts allocate a new file group and write its first slice for that file group. These file slices and their commit instant times are color coded above.

SQL queries running against such a table (eg: select count(*) counting the total records in that partition), first checks the timeline for the latest commit

and filters all but latest file slices of each file group. As you can see, an old query does not see the current inflight commit's files color coded in pink,

but a new query starting after the commit picks up the new data. Thus queries are immune to any write failures/partial writes and only run on committed data.

The intention of copy on write table, is to fundamentally improve how tables are managed today through

- First class support for atomically updating data at file-level, instead of rewriting whole tables/partitions

- Ability to incremental consume changes, as opposed to wasteful scans or fumbling with heuristics

- Tight control of file sizes to keep query performance excellent (small files hurt query performance considerably).

Merge On Read Table

Merge on read table is a superset of copy on write, in the sense it still supports read optimized queries of the table by exposing only the base/columnar files in latest file slices. Additionally, it stores incoming upserts for each file group, onto a row based delta log, to support snapshot queries by applying the delta log, onto the latest version of each file id on-the-fly during query time. Thus, this table type attempts to balance read and write amplification intelligently, to provide near real-time data. The most significant change here, would be to the compactor, which now carefully chooses which delta log files need to be compacted onto their columnar base file, to keep the query performance in check (larger delta log files would incur longer merge times with merge data on query side)

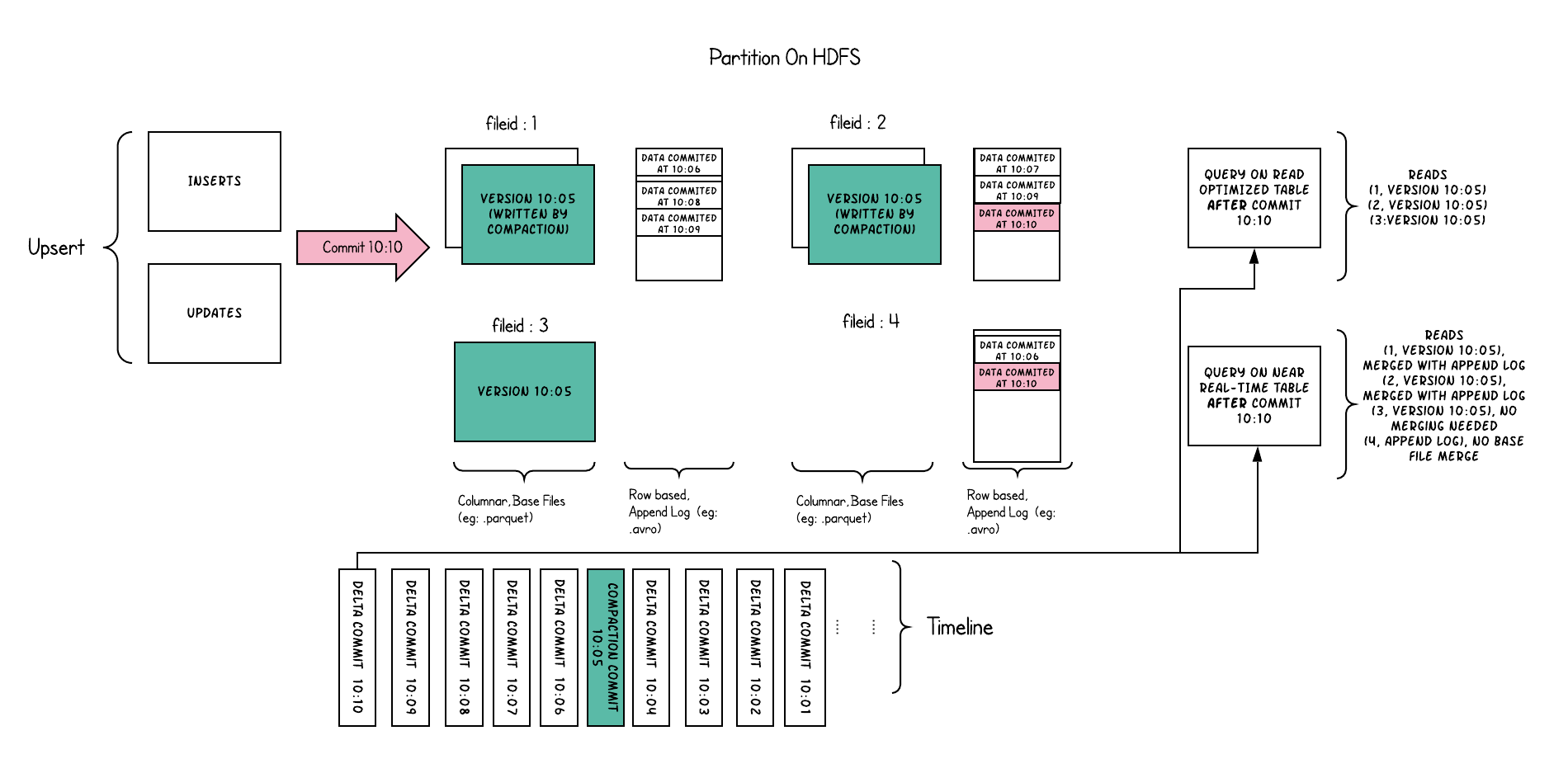

Following illustrates how the table works, and shows two types of queries - snapshot query and read optimized query.

There are lot of interesting things happening in this example, which bring out the subtleties in the approach.

- We now have commits every 1 minute or so, something we could not do in the other table type.

- Within each file id group, now there is an delta log file, which holds incoming updates to the records already present in the base columnar files. In the example, the delta log files hold all the data from 10:05 to 10:10. The base columnar files are still versioned with the commit, as before. Thus, if one were to simply look at base files alone, then the table layout looks exactly like a copy on write table.

- A periodic compaction process reconciles these changes from the delta log and produces a new version of base file, just like what happened at 10:05 in the example.

- There are two ways of querying the same underlying table: Read Optimized query and Snapshot query, depending on whether we chose query performance or freshness of data.

- The semantics around when data from a commit is available to a query changes in a subtle way for a read optimized query. Note, that such a query running at 10:10, wont see data after 10:05 above, while a snapshot query always sees the freshest data.

- When we trigger compaction & what it decides to compact hold all the key to solving these hard problems. By implementing a compacting strategy, where we aggressively compact the latest partitions compared to older partitions, we could ensure the read optimized queries see data published within X minutes in a consistent fashion.

The intention of merge on read table is to enable near real-time processing directly on top of DFS, as opposed to copying data out to specialized systems, which may not be able to handle the data volume. There are also a few secondary side benefits to this table such as reduced write amplification by avoiding synchronous merge of data, i.e, the amount of data written per 1 bytes of data in a batch