Maximizing Throughput with Apache Hudi NBCC: Stop Retrying, Start Scaling

Data lakehouses often run multiple concurrent writers—streaming ingestion, batch ETL, maintenance jobs. The default approach, Optimistic Concurrency Control (OCC), assumes conflicts are rare and handles them through retries. That assumption breaks down in increasingly common scenarios, such as running maintenance batch jobs on tables receiving streaming writes. When conflicts become the norm, retries pile up with OCC, and the write throughput tanks.

Hudi introduced Non-Blocking Concurrency Control (NBCC) in release 1.0, solving this problem by allowing writers to append data files in parallel and using the write completion time to determine the serialization order for reads or merges. We'll explore why OCC struggles under real-world concurrency, how NBCC works under the hood, and how to configure NBCC in your pipelines.

The Problem with Retries

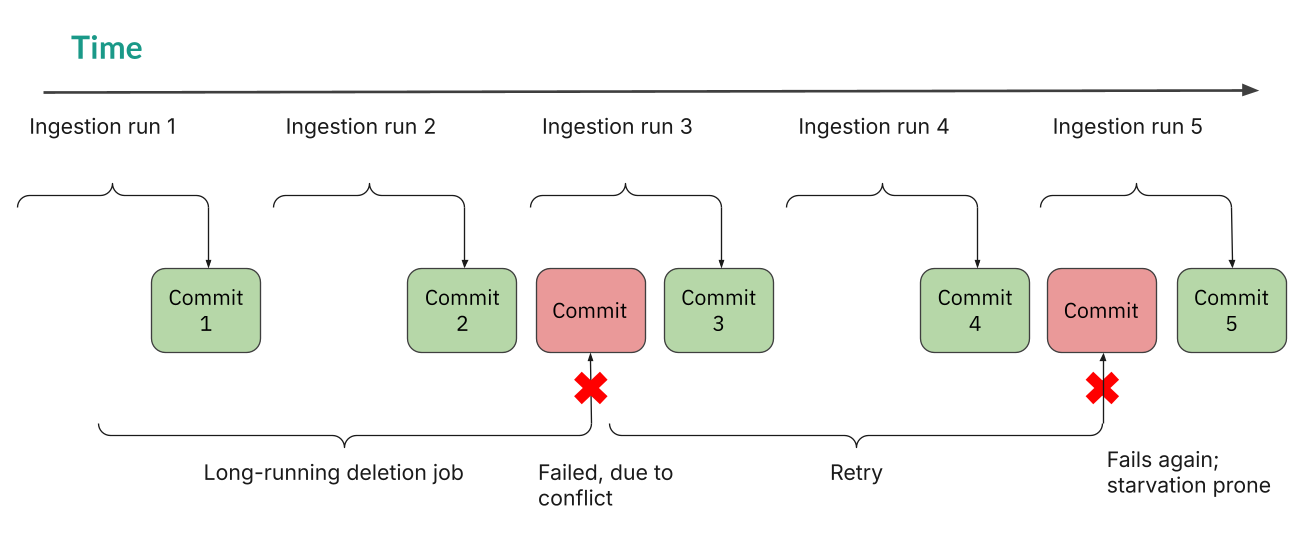

Picture this scenario: your streaming pipeline ingests clickstream data every minute from multiple Kafka topics. A nightly GDPR deletion job kicks off at midnight, scanning across thousands of partitions to purge user records—also touching data files the ingestion pipeline is actively writing to. By 3 AM, you get paged—the deletion job has failed repeatedly, burning compute resources while the ingestion writer keeps winning the race to commit.

OCC assumes conflicts are rare—an assumption that held in traditional batch-oriented data lakes where jobs were scheduled sequentially. Most transactions will not overlap, so let them proceed optimistically and check for conflicts at commit time. But high-frequency streaming breaks this assumption: when you have minute-level ingestion plus long-running maintenance jobs, overlapping writes are not the exception—they are the norm.

This is a classic concurrency anti-pattern: under OCC, conflict probability grows with transaction duration. Long-running jobs competing against frequent short writes lose nearly every commit race and retry indefinitely. When both concurrent writers are running ingestion, without careful coordination between the writers (e.g., segregating writers by partitions), the consequences become more severe: conflicts occur more often, overall throughput is reduced, and compute costs increase. The key insight is that retries are the throughput killer—we need a fundamentally different approach.

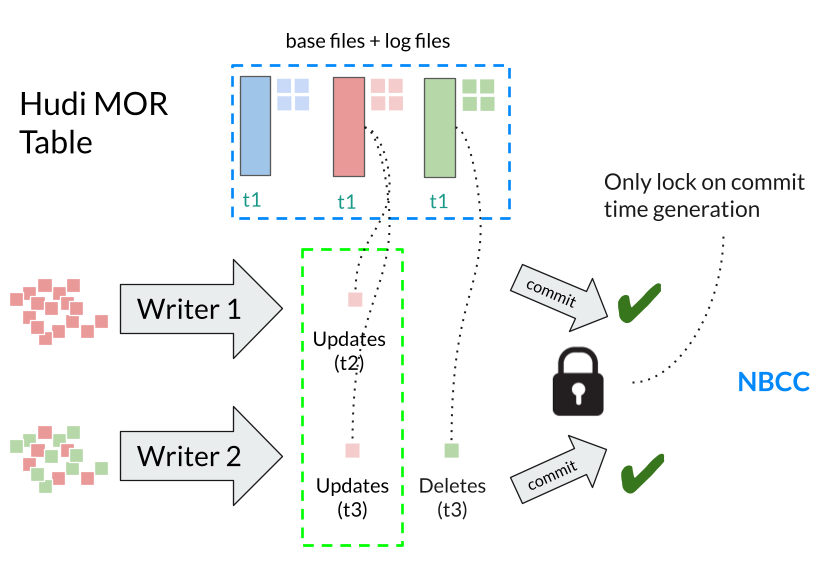

Hudi NBCC: Write in Parallel, Serialize by Completion Time

NBCC avoids conflicts by design: let every writer append updates to Hudi’s log files in the Merge-on-Read (MOR) table, then let readers or mergers follow the serialization order based on write completion time. Let's say there are two writers, both updating a record concurrently. Under NBCC, each writer produces its own log file containing the update. Since there's no file contention, there's nothing to conflict on. At read time or during compaction, Hudi follows the write completion time and processes the associated log files in the proper order.

Both OCC and NBCC require locking—OCC during commit validation, NBCC during timestamp generation. The key difference is how long the lock is held, and what happens after. OCC holds the lock while validating: for concurrent commits, it compares the sets of written files to detect conflicts—so validation time grows with both transaction size. If validation detects a conflict, the losing writers discard their completed work and retry. NBCC's lock duration is a negligible constant (a configurable clock skew duration, 200ms by default) regardless of transaction size: acquire lock, generate timestamp, sleep for clock skew, release. No file-level validation, no conflict detection, no retries.

| OCC | NBCC | |

|---|---|---|

| On conflict | Abort and retry | No conflicts—each writer appends separately |

| Lock duration | Scales with the number of written files to validate | Constant (brief clock skew duration) |

| Resource waste | High | Nearly none |

Hudi supports both OCC and NBCC for multi-writer scenarios. Hudi also offers early conflict detection for OCC, which can reduce wasted work by failing faster. However, OCC's validation lock duration still exceeds NBCC's timestamp generation time, and retries still occur after conflicts are detected—both impacting overall write throughput.

How NBCC Works Under the Hood

Hudi NBCC relies on several design foundations to enable conflict-free concurrent writes and maximize throughput.

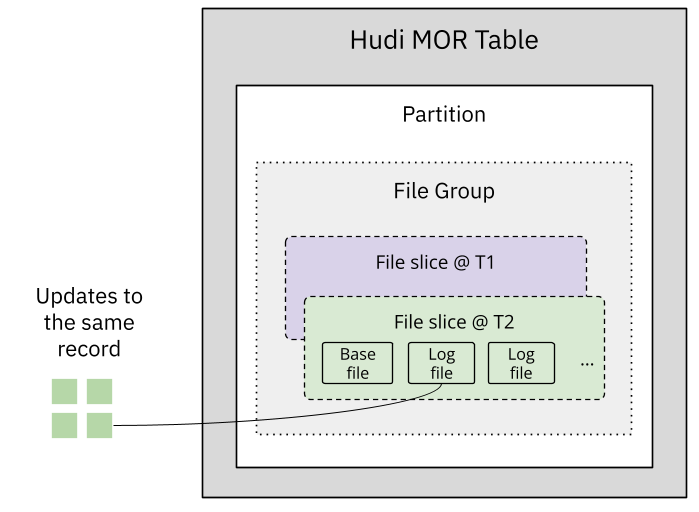

Record Keys and File Groups

Hudi organizes data into file groups, where records with the same record key always route to the same file group. Hudi uses indexes to efficiently route records to file groups. For MOR tables, updates don't rewrite base files—instead, writers append updates to log files within the file group.

This record colocation is a key foundation for making NBCC possible. Records and their updates will always be routed to the same file group based on record keys, either in base files or log files—all associated with the same file ID that identifies the file group. The record key to file group mapping and the file ID association support read and merge operations by efficiently locating files to process. Also, concurrent Hudi writers use timestamps and write tokens to generate non-conflicting file names within each file group, and thus data writing can be non-blocking.

Completion Time: Serializing Concurrent Writes

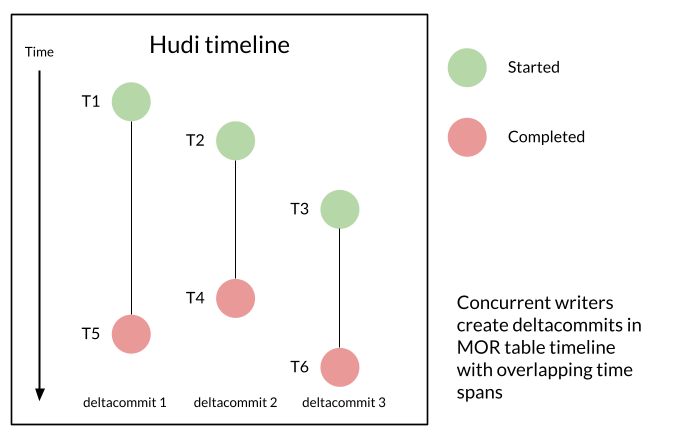

With NBCC, concurrent writers produce log files whose write transactions overlap in time. To process these files correctly, we need a proper serialization order. Consider: Writer A starts deltacommit 1 at T1 and completes at T5; Writer B starts deltacommit 2 at T2 and completes at T4. If we order by start timestamp, deltacommit 1 would be processed first—but it actually finished later than deltacommit 2. Completion time reflects the correct order for processing the files.

Tracking the completion time is critical for NBCC. Concurrent writers flush records to files in parallel without any guarantee of completion order based on the start time. Hudi timeline tracks when each write is actually completed, enabling the correct serialization order for the writes.

TrueTime-like Timestamp Generation

Distributed writers running on different machines face clock skew—their local clocks may differ by tens or even hundreds of milliseconds. Without coordination, two writers could generate the same timestamp or produce incorrect ordering.

Hudi solves this with a TrueTime-like mechanism inspired by Google Spanner:

The process works as follows:

- Acquire a distributed lock

- Generate timestamp using local clock

- Sleep for X milliseconds

- Release lock

The sleep accounts for the worst-case clock skew between writers. By waiting longer than the maximum expected skew before releasing the lock, Hudi guarantees that any subsequent writer will generate a strictly greater timestamp.

These monotonically increasing timestamps ensure that concurrent writers never produce conflicting or out-of-order commits—achieving transaction serializability and completing the foundation for NBCC.

Supporting Designs

In scenarios suited for NBCC, we may encounter long commit histories and need to properly merge records. Hudi 1.0 introduced two supporting designs that complement NBCC.

LSM Timeline: High-frequency streaming can produce millions of commits over time. Listing and parsing individual timeline files would be prohibitively slow, and the storage overhead can become a headache. Hudi timeline uses an LSM Tree structure—archiving older commits into sorted and compacted Parquet files for efficient lookups and reduced storage footprint.

Merge Modes: When log files from concurrent writers need to be merged during reads or compaction, we need proper record-merging logic. Hudi supports flexible merge modes that control how records with the same key are resolved—whether to keep the latest by commit time, respect user-defined ordering fields, or apply custom merge functions.

Using NBCC

With the design foundations covered, let's see how NBCC works in practice.

NBCC in Action

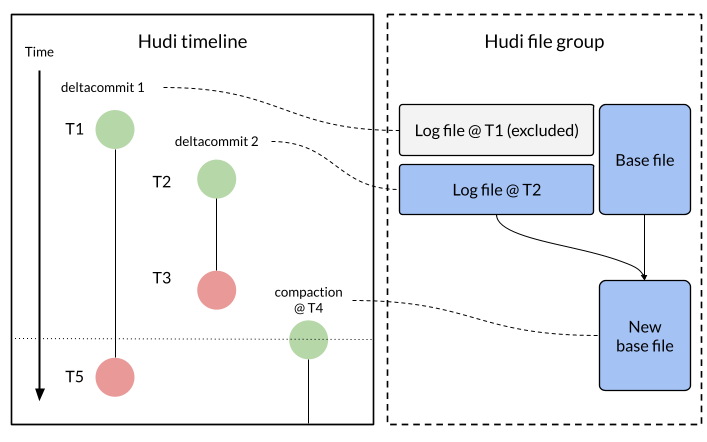

NBCC allows concurrent writers to append data to log files in a non-conflicting way. Subsequent read or merge operations will need to follow the write completion time to process the files. Take compaction as an example, as shown in the diagram below.

Consider two writers: Writer A creates deltacommit 1 (starts at T1, completes at T5); Writer B creates deltacommit 2 (starts at T2, completes at T3). When compaction is scheduled at T4, the planner only includes files from deltacommit 2, since its completion time (T3) is earlier than the compaction schedule time (T4). Deltacommit 1, though started earlier, is excluded because it hadn't completed yet when compaction was planned—its files will be included in a later compaction.

Snapshot reads follow the same rules. A query at T4 includes data from deltacommit 2 but excludes deltacommit 1, which hasn't finished yet. A query after T5 includes both deltacommits, with log files read in completion time order and records merged according to the configured merge mode.

Configuration

NBCC requires Hudi 1.0+ and a lock provider for TrueTime-like timestamp generation. Common options for lock providers include ZooKeeper-based and DynamoDB-based, which integrate with existing infrastructure many organizations already run. Hudi 1.1 introduced the storage-based lock provider, which uses cloud storage conditional writes (S3, GCS) and requires no external server—an option with less operational overhead for cloud-native deployments.

hudi_writer_options = {

'hoodie.write.concurrency.mode': 'NON_BLOCKING_CONCURRENCY_CONTROL',

'hoodie.write.lock.provider': 'org.apache.hudi.client.transaction.lock.StorageBasedLockProvider',

}

To enable NBCC for your concurrent writers, configure the concurrency mode and lock provider options for each writer, as shown in the example above.

When to Use NBCC

If you are running multiple concurrent streaming writers, or running streaming ingestion with batch maintenance jobs like GDPR deletion, NBCC is more suitable than OCC. The table below summarizes some common examples:

| Use Case | Recommendation | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Batch ETL with single writer or multiple coordinated writers | OCC is fine | No concurrency conflicts |

| Multiple concurrent streaming writers | NBCC | Avoid retry storms |

| Mixed streaming + batch maintenance | NBCC | Long-running jobs will not starve |

| Copy-on-Write (COW) tables with infrequent updates | OCC is fine | COW rewrites base files anyway |

| MOR tables with frequent updates | NBCC | Maximum benefit from log file separation |

Hudi NBCC is designed specifically for MOR tables. COW tables rewrite entire base files on updates, so file-level conflicts are unavoidable regardless of concurrency control mode. As of now, NBCC is restricted to working with tables using the simple bucket index or partition-level bucket index. Learn more from the concurrency control docs page.

Summary

OCC assumes conflicts are rare. When you mix high-frequency streaming with long-running maintenance jobs, OCC's retry-on-conflict model breaks down—causing wasted compute, reduced throughput, and job starvation. Retries are the throughput killer.

NBCC takes a different approach: let every writer succeed by appending to separate log files, then follow the write completion time for reads and compaction. Three design foundations make this possible—record keys and file groups that colocate records and their updates, completion time tracking that properly orders overlapping write transactions, and TrueTime-like timestamp generation that guarantees monotonically increasing timestamps across distributed writers.

The result: maximum throughput for concurrent writes in Hudi pipelines. Long-running jobs complete without being starved, multiple ingestion pipelines coexist without contention, and your data platform scales without coordination overhead. Stop retrying, start scaling—see the docs to get started.